Nige and I met to talk about his writing career and memories of Word in a London pub in December 2018. During a quick chat before we began the business at hand, we discussed transcribing, editing and reordering interviews. Nige told me a piece of advice he learnt from someone who knows a bit about it. “Something David Hepworth always told me is that no-one ever sued a journalist for making them sound better than they are.”

I really enjoyed reading Butch Wilkins and the Sundance Kid. It seemed to that your childhood was a struggle for supremacy between music and televised sport. Is that how it felt for you?

I’ve got a theory that the boys who didn’t buy Warlord comic or have Action Men get into football and become mad about that. About three years after that they get into music. They’re two very similar passions. At 9, 10, 11 I was crazy about football and then I started buying Smash Hits in 1981. Suddenly I’m asking ‘Oooh, who are Department S? Who are the Teardrop Explodes?’ And we all know who the guiding lights of that magazine were. So it was a struggle for supremacy but it was cooler to like music. At school I kind of floated between the slightly nerdier kids who played with a tennis ball in the playground and the ones at the other end who had an Our Price bag glued to their wrists, like I did. As I got older I‘d be hanging out more with the music gang. In the mid-eighties sport wasn’t cool. It was a dire time for football but a good time for music.

So sport was more of a private passion?

Yes, the book’s about me spending my teenage years indoors. I didn’t run off in my school uniform to follow Aztec Camera around like Pete Paphides might have done. I was stuck at home watching the RAC Lombard Rally. There was lots of snooker and darts too. Then I started playing snooker – that’s another story about how I fucked up my A levels by spending time down at the snooker hall instead of revising. That’s a tale for another book.

It was very evocative of that period. I was born in 1970 and I’d forgotten how large a part televised sport played in my young life. It seems odd now but people like Jonah Barrington, June Croft and David Bryant were quite big names then. I doubt many people could name a squash player or a bowls champion these days.

I was wondering if it was just me, if it was just because that’s when I was absorbing it. My kids wouldn’t know it because it’s not on terrestrial TV. As much as the book is a bit of a nostalgia-fest, it’s also about teenagers. It’s a bit like Fever Pitch, but rather than doing anything remotely heroic like standing on the terraces and watching a match, the most adventurous I get is popping downstairs to the biscuit tin. I don’t think we realised we were in that golden age of terrestrial TV. Everything was there on tap and you presume that this is how the world will always be. As soon as I bought a portable telly with the proceeds of my paper round, it was all at the flick of my big toe because the set was at the foot of my bed and I could switch channels that way. It was all I needed. It never seemed to coincide with music. The Tube was on Friday evenings, 5:30 until 7:00. There wasn’t any sport on then, but there might be some live athletics on around 8:00. Whistle Test was 8:00 on BBC2, that didn’t clash with anything midweek. They were able to coexist, they could dovetail in terms of my TV consumption and I could fill in any gaps by playing records. And then, if some sport is on, off comes Echo & The Bunnymen and on goes Sid Waddell!

It’s interesting to track the changes too, like the televised live football games. The BBC get them for a while but then they can’t afford them. They didn’t feel like big changes at the time.

No because it was between two terrestrial channels. Either way was fine. I can see it with Moore and Tyler or Motson and Davies. Seeing a whole live game that wasn’t a cup final but a normal, run-of-the-mill league match was great. You’d have Sunday Grandstand from May to September, during the cricket season, but during the football season that would largely disappear. There was little Sunday sport on, unless there was a snooker or darts tournament on. So having live football suddenly on a Sunday afternoon was great. But there’s something in people not having much choice. They value things a lot more. I barely watch any live football matches now. I don’t have Sky or BT Sport, I watch the highlights on Match of the Day. If I wanted it I could get it, but it’s something to do with too much choice. In the eighties we had shared experiences and that wouldn’t necessarily happen now.

It also got me going back to listen to old theme tunes and sporting clips. Some I remembered, some I didn’t know like the guy (Randy Mamola) who comes off the motorbike and gets back on.

When you’re sat at the kitchen table at 11 at night, your wife is asking if you’re coming to bed and you say you’re doing book research and you’re watching a Midweek Sports Special from 1983 because you need to find out who wrote the theme tune… The music for certain things like the tune for Mexico ‘86 which was then used for The Big Match and Saint & Greavsie. That was prickly skin moment, that tune is hard-wired into me even though I’d not heard it for years. I could even remember the footage clips from the intros and what would happen in them. It was all in the back of my head, doing absolutely nothing. It’s all there, under a layer of dust so you have to put it to use by writing a book about it.

You mentioned Department S and the Teardrop Explodes earlier. When did music start becoming a larger part of your life?

I certainly had no help from my parents’ record collection which was just appalling. They had Abba’s Arrival which was about their only remotely contemporary album. They had a New Seekers one but it wasn’t the normal square sleeve – it had all these flaps you had to put in a certain order. That fascinated me more than the contents of the record. The first album I bought was the cassette of ELO’s New World Record when I was on holiday with my gran, down by the seaside in 1978. She thought I was a bit strange getting an album by an orchestra at the age of seven. It’s only in the last six months that I’ve realised I bought it because I liked Fanfare For the Common Man – by ELP not ELO! But I ended up loving ELO, they were my first proper band. Later on I got into all the Liverpool bands like the Bunnymen and the Teardrops. I’d look at all the WHSmiths adverts in Smash Hits for £3.99 albums. Post-punk was called ‘Bleako’ where I came from.

Bleako?

Yeah, as in bleak – if you like bleak music, you’re a bleako! Then I saw the Smiths on TV in 1983, playing This Charming Man on the BBC2 arts show Riverside. I’d seen their name in the indie charts in Smash Hits and thought it was something to do with Mark E Smith. I was only aware of Mark because there was a mention of him in the book Liverpool Explodes by Mark Cooper. I’d never heard of The Fall so I thought it must be his band.

Must be him and his brothers and sisters?

Exactly, a family like the Osmonds! So, I rushed out and bought This Charming Man and Hand In Glove and the rest of the seven inches as they came out. I got into R.E.M quite early as well just before Reckoning was released. They were my twin loves. I wasn’t a big Peel fan because he was on a bit late for me and I had paper round to get up for in the morning. The biggest influence on me was Janice Long, her Saturday night programme. I could stay up, it wasn’t a school-night and she wasn’t as wilfully obscure as Peel. That’s where I first heard James Brown and a lot of post-punk stuff. In about ’88 I got into Andy Kershaw, even though he was a couple of years into his Radio One tenure then and discovered African music through him.

I graduated from Smash Hits to Q, via NME. I liked Q because of the humour, but I could have done without so many Mark Knopfler and David Gilmour covers. But it was perfect-bound and really collectible with the numbered issues. With the Tom Hibbert stuff, it was entertainment rather than a way for me to discover new bands like the NME had been.

My degree was American Studies and my dissertation was about how black music had been co-opted into the white mainstream. It was called Are You Ready For a Brand-New Beat? I thought it was so clever! I started getting into a lot more black American music then.

Where were you living then?

I was at Essex University and stayed there after graduation. We then had a few months on the dole and housing benefit. At that point I was writing for a little blues magazine called Blues & Rhythm done by some lads in Lancashire. They’d send me a four-hour tape of an interview with some obscure bluesman whose accent was impenetrable. I didn’t have a computer then, so I’d be writing out pages and pages of it and thinking ‘Is this journalism?’

Then we moved to Bristol and I started working for Venue magazine, Bristol’s equivalent to Time Out. I’d been reading it for a couple of years – it was high-quality and well written. Eventually a job came up as one of the music editors – well, seven hours a fortnight collating the listings. I did that for a couple of years and was then appointed editor. That was my first job in publishing, editing a fortnightly 152-page magazine with, thanks to pages and pages of listings, a really high word count. I had no experience. I really was in at the deep end, but did that for three and a half years. I think fortnightly is the best frequency for a magazine – see here Smash Hits and Private Eye. There’s not too much pressure to read it there and then, but each issue comes around fairly quickly. There can be a disconnect with a monthly magazine; you might read it for the first ten days and then stop thinking about it.

Then Venue got taken over by the Bristol Evening Post who wanted to make turn it weekly. But there was no extra staff or money. It was a real cottage industry, it was crazy. Everyone has some kind of job where they have a formative experience and that was mine. We would always be late, always chasing our tail. So many times I’d be locking up the office as the milk float was going down the road at dawn or I’d have to meet a courier at four in the morning in a lay-by somewhere on the road to Avonmouth to hand the processed film to a courier on a motorbike. It must have looked really suspicious.

At the point when I was getting really cheesed off with it, I got head-hunted by the publisher who put HMV Choice magazine together. It was their in-store magazine that covered their specialist departments – classical, country, soundtracks, folk, jazz, world music and all that kind of stuff. They took me to lunch and said “It’s five issues a year. Could you deal with that?”. Having come from a job where I was doing 51 issues for significantly less money, I thought I might just be able to! It wasn’t the pinnacle of music journalism, but it was steady and I interviewed lots of great people. It was at that point I started getting involved with Word because I suddenly had evenings and weekends free again.

I remember writing to Mark Ellen who I’d met once before through Andy Kershaw at WOMAD. I asked if I could interview Green from Scritti Politti as they had a new album out. Jude Rogers wrote back asking me to the review that album as that was the message Mark had given her. But it was a foot in this very significant door. That was when they did those 250-350-word standard reviews, rather than the 150-worders, so you could get your teeth stuck into them. This was 2006 and I reviewed stuff for them for another four or five months before graduating to features. I started doing features I could put together easily, ones where I didn’t need to take time off from the day job to go and interview people. I did one about famous ex-flatmates – Dustin Hoffman sleeping on the kitchen floor of Gene Hackman’s apartment, that kind of thing. I could pop out at lunchtime and go into a bookshop or library and look things up. I did these type of features for a while but didn’t want to get pigeon-holed as the guy who only did that.

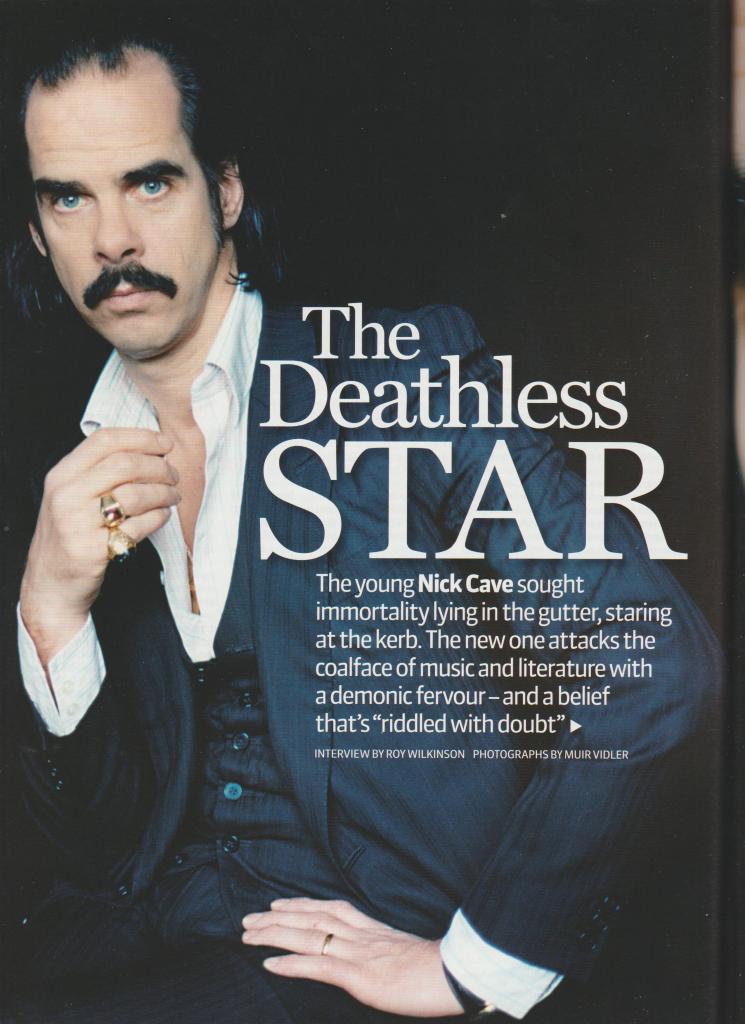

The first proper interview I did was with Seasick Steve. I went and spent some time with him at the End Of The Road festival, around the wood-burning stove in the back of his van. and it was my first job I did with WORD photographer Muir Vidler, who took some great pictures. Andrew Harrison was looking after features at WORD at that point. He’s a great editor, but quite a tough one who’ll tell it like it is. After I filed it, I got an email back an hour later. “Nige, this is fucking great! Going to give it some more pages.” Had I done a shit job on that, I’d have been off features.

So I carried on doing whatever interviews were needed. I was reliable and versatile, someone who would put the research in, do a solid job and deliver it on time. I was at a slight disadvantage not being London-based unlike a decent majority of their writers. I was in the wilds of Somerset by then. If they asked “Could you interview Dodgy at the Royal Festival Hall?”, I couldn’t say “That’ll cost me £70 on the train. Are you going to pay my expenses?” because they’d just get someone who lived three tube stops away to do it instead. You just have to suck that up and be dedicated to the cause, but by doing that you get more and more. And when you heard from Mark saying he had an idea and you were the person he had in mind – that’s a nice feeling. These were the guys who introduced the concept of music journalism to me, so to be writing for them was an honour and a privilege.

Mark was an amazing editor – the best I’ve ever written for. As bouncy and up as he is, if he didn’t like something he’d tell you. “You need a stronger opening. Can you go back and fix?” What you couldn’t do with Mark was say “Do you want 700 words on this singer/writer/comedian?” Other editors might accept that to fill up some space but Mark would always ask “What’s the angle?”. He wanted it summed up for the two sentence strapline so readers knew where the piece was coming from. Otherwise it’s just “blah blah blah, they’ve got an new album out, blah, blah, blah…”. Mark always made it sharper by drilling down. When he started doing those pieces inspired by The New Yorker that rolled into each other, they lived or died on that little strapline. They had to pique your interest and tell you why you needed to read it. The genius of Word was that they put the effort in and created their own identity and their own take on things. They didn’t kowtow to the PR wanting to focus on certain things. They had their own ideas. They had a lot of goodwill in the industry so they could get some amazing interviews.

What was your favourite piece that you wrote? You mentioned Seasick Steve earlier.

I’ll treasure that one because it opened the door. It was always good when you went on assignment, especially for someone who was largely home-based. The day I spent in the Test Match Special commentary box was great. We walked in there and it was a cavalcade of famous faces. I remember seeing Jeff Thomson and then Geoffrey Boycott came in. Muir, the photographer, was with me again and he had pretty much a ginger afro at the time. Boycott just says to him “Curly hair that.” We filled our boots at the buffet, then Stephen Stills from CSNY turned up as the lunchtime guest. I counted about seven or eight England captains, and also grabbed Phil Tufnell for a quick chat. We made ourselves scarce when all the bosses came in, wandered along the gantry and found an empty little studio with just a couple of chairs and a desk. We sat there watching England against Australia in a one day international with the best seat in the house. Afterwards I asked the producer about the empty studio. “Oh, that’s the TalkSPORTstudio. Jack Bannister doesn’t like leaving home so he watches it on the telly and phones his update in every quarter of an hour.” So we stayed there!

I’d been doing the HMV job until the end of 2008 and we’d had two kids by then. I’d been getting plenty of freelance work without really trying so I thought I should go for it and go solo. In the first month I had the offer of a trip to Mali on a junket. I asked Mark if he fancied a piece on it and he said he could give me a couple of pages. I thought it wouldn’t be enough to justify the record company flying me to Mali via Paris. A few days later, though, the record company said it was on, so I had a couple of days to get all my jabs done and suddenly I was off. This was my first month as a freelance. I’d also interviewed Michael Sheen that month and then I was sitting with a G&T and my feet in a pool in Mali in January. It felt like going freelance was the right decision.

I got to interview a load of people for Word. Every month I was doing a good chunk for them. The beauty of it was that 90% of them were down the phone line so I could do the work from Somerset at no disadvantage.

And you finally got to speak to Green.

I did, for WORD’s final issue as part of an article on squats. I interviewed Boy George for that too. I remember talking to him while I was pushing my son around the aisles of Morrisons. George apologised for being in an airport departure lounge. “That’s ok. I’m in the supermarket doing my shopping.”

What are some of your memories of those interviews?

I’m almost certain to be the only person who travelled to The Ivy by National Express coach. I was there to interview Rebecca Front.

I can always remember where I interviewed people when I do phone interviews – quite often it’s sitting in my car in the driveway. It’s better reception and it’s quieter than the house. For Santigold, she was in the US and I really wanted a clear line so I found a summer meadow up on the Mendips to call her from. We chatted about our respective love of the Smiths. There are worse ways to earn a living than that.

They’re not always straightforward. WORD ran a big piece on Ian Dury on the tenth anniversary of his death – Paul Du Noyer wrote the main tribute and Mark asked me to speak to a load of people and get one anecdote from each one. That way you’d get a rounded portrait of a complicated character. I remember interviewing Sinead O’Connor for that. At the time I had a desk in an office that I was sharing with a PR company. They were loud and sparkly so I had to say “I’ve never asked you to be quiet but can you be shut up? I’m about to interview Sinead O’Connor.” One of them shouts “Everyone be quiet! Nige is on the phone to Sinead O’Connor.” The room goes silent with everyone now listening to my bumbling interview technique. And it was a classic.

“Sinead, it’s Nige from Word.”

“Hang on…I’ve just got a bit of fish in my mouth…. OK, it’s gone now.”

“So what I’m doing is speaking to people who knew Ian Dury.”

“Yeah, I met him once. He seemed alright.”

“Have you got a bit more?”

It turned out there was nothing else – she didn’t make the cut! But I got to speak to Peter Blake, a few of the Blockheads and Phill Jupitus.

I was due to interview Richard Ayoade about Submarine, the first film he directed. I watched it at the film distributors in Soho and was due to speak to him afterwards. I was in the viewing room on my own and I could sense this presence. I looked up and he was watching me through the window to see if I was laughing.

I used to do a lot of the Word Of Mouth pieces, favourite books, films and music. They were easy to do; it’s a 20-minute thing I can do from home and you got to speak to loads of great people. As long as the PR had prepared them, which hadn’t always happened, they were straightforward. One comedian said “Oh, you’re joking, is this what it is? If I hang up, that’s it, don’t call back.” We managed to get to the end of the interview and it was all fine.

The worst thing is when they name something you don’t know like “You know that lost Nick Drake album?” or some obscure band and you say “Oh yeah, yeah, I think so…” After the event I’d be trying to phonetically decode what they’d said. Sometimes you’d have to blag it a bit but otherwise it was good fun. Twenty minutes to do the interview, an hour to transcribe it, a quick tidy up – nice job! I’m just wondering if any of them were bastards but none of them were. Word only chose the good people. The most difficult was probably Ayoade, just because he’s painfully shy. Normally with comedians you can’t shut them up!

I’d thought it was a bright, warm day when I sat on the banks of the Regent Canal with Tim Minchin to interview him, but it was deceptively cold. God, I must have seemed so unprofessional. The batteries on my dictaphone were going and he said “Don’t worry, I’ll record it on my IPhone and send it on”. Then he noticed me shivering and offered me his coat. “You’re literally shivering, let’s go back inside!” Just because they’ve got a public profile doesn’t mean they have to be distant

So what happened after Word closed?

I see Word as the highpoint of my career really. I was still doing things for them up to the end, including the sleeve-notes for the free CDs. Half my income as a freelancer was coming from them every month at that point so it was a JFK moment when I heard the news. I was putting the WOMAD programme together when I got an email from Mark and I just thought ‘Oh, bloody hell!’ I was obviously sad for my mortgage repayments – but more so for the staff there and just sad that it wouldn’t exist anymore. It was the best magazine and I’m not just saying that because I wrote for them. I would read it cover to cover, even the interviews with people I didn’t massively care about. I’ve got all the back issues at home. Other magazines have come and gone, been put in the recycling bin, but I’ll never get rid of those. I had as much enjoyment from reading it as I did from writing for it, something I’ve never really had that with any other magazines. I’d advise anyone to go back and read them again, the quality of the writing is brilliant. All the editors weren’t just editors, they were great writers too.

God bless ‘em!

I loved it, I miss it so much! It’s about six years now since it closed and enough distance has gone that I feel a bit detached from it. When I leaf through them again, it brings back a lot of memories.

Did you appear on many of the podcasts?

I did – number 204, not that I have memorised it… I’m delighted to report that, of all the podcasts, it was the longest. I out-spoke Danny Baker. Can you believe that?! It was mainly because I brought some cider up and the tasting took up a bit of time. It was a privilege to go to that glorified clothes cupboard that doubled as the recording studio and row out to Bollocks Island. I appeared at a Word In Your Ear too when my first book came out.

Was it fun doing the podcast?

Absolutely, yes. I’d done a retro piece on cassettes and cassette culture with some great pictures that people had sent in. I went in to talk about tapes but that was only twenty minutes of the hour and a quarter. A lot of it was trying to get a word in – Mark and David were both in full flow. David arrived with three coffees and I’d already had an energy drink walking up Pentonville Road so I was ready.

You were fired up?

You had to be. I’ve been on the radio with Danny Baker and it’s the same with him. You can’t be a passenger or spectator. You have to grab hold and stay with him.

In the ways that the magazine stands up to repeated reading, the podcasts stand up to repeated listening. Some of them will date – I think there was one asking ‘What’s an iPod?’ As documents of the shifts in popular culture in the last 15 years, they’re really interesting. You’d have your favourite ones when certain people were on there but they were all good for a listen.

Do you listen to many other podcasts these days?

Not so much – I’m working a lot from home now after a couple of years of lecturing on journalism.

How did you get into that?

I knew someone who was already lecturing there and he said “They need some lecturers, you should do that.” I wasn’t sure but it was steady income and as a freelancer, that’s rare. I went for the interview and they said they wanted me to do a couple of days a week teaching magazine journalism and sports journalism. I went to a meet and greet after these academics had been off for several months for the summer and someone said, “Oh, Jude can’t make it today I’m afraid.”

“Who’s Jude?”

“Jude Rogers.”

I thought, ‘This is alright, my old Word pal’s Jude’s gonna be here!’ She’s still there but I left after a while as the workload was immense. There was a lot of admin, marking, personal tutoring and I really wanted to be writing. Plus it was a 140-mile drive on the M5 which on a Friday is one of the pits of hell. I got Barry McIlheney and some sports people down to talk to the students which was good fun.

Lecturing’s not something I’d rush back to, but it gave me the ability to stand up in a busy room, read aloud from a book and answer questions. I’ve done a few literary festivals since then so at least it gave me practice of being in front of a load of people. And shingles. Yes, it also gave me shingles.

While we’re talking about books, what was the first one?

That was Mr Gig. When I was at university I made a bee-line for the Ents Office and somehow got elected as the Ents Officer the following year. I put on bands like Lush as the support for the House Of Love. That night, Alan McGee came and knocked on the door saying, “You need to get some beers for the girls, you’re only giving them £50.” I gave them half a crate of Skol. I’ve since apologised to Miki for that. She said, “It was fine, we didn’t normally get paid at all.”

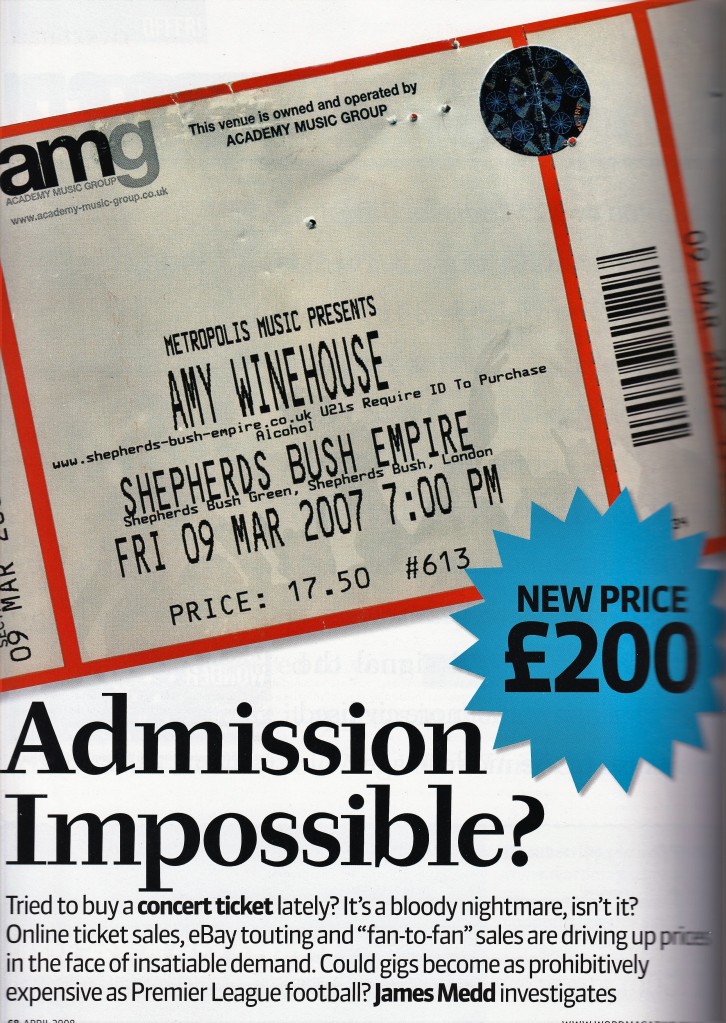

My first job between graduating and being on the dole was a summer spent being a roadie. Then I put on a few gigs and did some DJ-ing as support to bands around Bristol. Once I moved out of Bristol to the country and had kids, I felt divorced from live music. Gigs used to be a dirty subculture that I went to as a seventeen year old and now several generations of families go to bright, shiny arena shows. Gigs are big business and the record industry isn’t, so I tarted this up into the premise of a book and went off trying to re-engage with live music. I went to see bands like The Wedding Present and Half Man Half Biscuit. I also went to a death metal festival and a cheesy 80’s pop nostalgia fest where everyone’s wearing shoulder pads or dressed in Ghostbusters outfits. That was immense fun and I got to interview loads of 80s people. They all were at ease with it and were happy to be playing their one hit in front of twenty thousand people – where else would they be able to do that?

It’s an audience and you’re getting paid.

Exactly.

The one ambition I had in life was to have a book published – and I’d done that. It’s good as a magazine journalist to have something coming out at the end of the following month but writing a book and seeing it on the shelf, knowing it won’t get chucked out in the recycling bin, is pretty addictive. With music, there aren’t many books left to write. If you’re interested in a particular band, you need them to have been around for a decade.

So I moved into sports books. I was writing for the football magazine FourFourTwo then which was a good gig because they’re all young lads in their late twenties/early thirties and I’m not. I remember stuff from the late 70s and early 80s that they know about but that they didn’t live through. It’s all in here (taps head) – I could write a feature from just what’s in my brain. I was the old fart coming up with these ideas, which I’m still doing.

I then wrote The Bottom Corner about non-league football. It was similar to Mr Gig in some ways – I like the idea of road trips and getting out and about. It adds colour to a piece. That’s what I liked when I did the Seasick Steve or Test Match Special pieces for Word, collecting colour and observing. It’s not just, ‘Here are the words from an interview, shuffle them around a bit.’ I went everywhere from Hackney Marshes to Tranmere Rovers who were in their first season out of the Football League in 92 years and lots of great stories in-between. I was chuffed when Waterstones put it on their list of top 12 sports books of the year.

Then I wrote a book on the 1989 Tour de France – Three Weeks, Eight Seconds. That race was an amazing story. Greg LeMond overturned a 50-second deficit on the last day and won by eight seconds. He had thirty buckshot pellets in his body from a shooting accident eighteen months earlier when he had been twenty minutes away from bleeding to death. I could have waited until the race’s thirtieth anniversary but I really wanted to do it, so we got in before anyone else plugged that particular gap on the shelves. And it got shortlisted for the Sports Book Awards, which was really gratifying. It’s since come out in the Netherlands, Spain and the US.

My next one is out in November. It’s about football’s transfer window.

You’re always thinking ahead aren’t you?

I have to. If I was working purely as a journalist and just did these books as an add-on, one every few years, it would be fine. I love doing them and need to do them financially. It’s tough being wholly freelance and pitching, pitching, pitching. Some of the pitches you can spend hours on and they never go anywhere. As a freelancer you have to very entrepreneurial. A book is a chunk of income and if I can do one a year that’s ok. And the clock’s ticking. I’ve just had a significant birthday that’s made me closer to sixty than forty. I remember when I was a kid, sixty was fucking ancient. So, that’s part of the thing of getting on with the books, keep going and try and get one out every year. Like The Redskins said: keep on keeping on.

Butch Wilkins and the Sundance Kid: A Teenage Obsession With TV Sport is out now. Nige’s next book – Boot Sale: Inside The Strange And Secret World Of Football’s Transfer Window – is published in November

Follow Nige on twitter here: @nigetassell

.

.